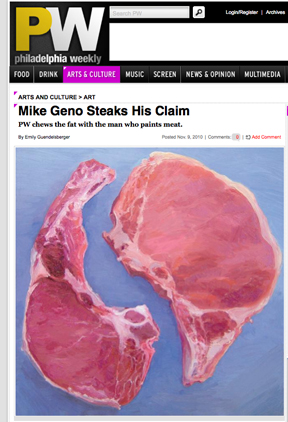

Mike Geno Steaks His Claim

PW chews the fat with the man who paints meat.

By Emily Guendelsberger

As the due date for his senior painting thesis approached back in 2001 in the Southern Illinois University MFA program, Mike Geno was a literal starving artist - he'd put himself on a ramen diet to conserve money for art supplies, for which he gave himself an unlimited budget. His thesis involved a lot of supplies, and he was going hungry and into debt rather than cut corners on materials. He'd joke with friends about using that budget to buy a big, juicy steak - using it as the subject of a still-life could justify the cost, and if he did it fast enough, he could eat it afterwards. He was thinking about one night's dinner, but as it turned out, his eventual follow-through on that joke would keep him fed for years to come.

The first one involved some logistics: How long can you leave a steak out under a lighting setup before it goes bad? Geno set up a carefully aimed air conditioner and a pre-mixed palette of reds and pinks, then bought the most attractive porterhouse he could find. He did the painting in about two hours, and after he'd finished eating the subject, he realized that the painting would actually fit into his thesis pretty well. He did 18 more paintings of other cuts of meat in two well-fed months, eating all the subjects except cubes of stew meat ("they turned color and I had to throw them away") and bacon, which he said didn't hold up.

A decade later, those same flimsy strips of bacon have supported Geno, now an adjunct professor at Moore, through bad economic times. "Etsy has been good to me," he says. His prints had been selling well, but the Internet-fueled bacon obsession of the last few years has made those prints his best-sellers by far.

Geno was pleased but baffled by the surge of interest in his bacon-based work. He's found meat aesthetically interesting since the early '90s, when he worked as a meat-cutter at a BJ's in the Northeast. It was his student job as an undergrad at Tyler and for several years afterward. He enjoyed the meat room, he says, because it paid well and there was "very little B.S., because the management didn't like to come in the meat room - it was cold."

The job gave him an interesting perspective on most people's objectifying relationship with meat, which tends not to be particularly realistic about a steak being a piece of a cow, rather than something that you pick off a steak tree. "They think of it as very abstract, they don't think of it as flesh or animal so much," says Geno, sounding ... oddly vegan.

When asked if he's ever been a vegetarian, Geno responds with a laughing "No. God, no!" Interestingly enough, he says, his vegetarian friends tend to like his meat series more than others, which he attributes to the noncartoonish way he depicts things.

"The texture of this raw flesh, the color changes where the light hits it or where the air is exposed more, the way fat marbleizes - these are all things that probably repulse a lot of my vegetarian friends," he says. His food paintings are meant to be honest, not beautiful - but that detailed honesty that can be mouth-watering to him can be seen as disgusting, too. "Maybe that's why it strikes them more."

Lately, Geno has shifted the focus of his food-based work from raw meat to things he finds interesting in a cultural way, although he says he only paints things that he finds both aesthically interesting and delicious (he'll probably never paint liver, he says). He's interested particularly in the nostalgia around bright, radioactive things like neon-orange peanut-butter crackers and mac and cheese and marshmallow Peeps, and in the layers of meaning involved in a city's hometown food. He has painted Philly foods like soft pretzels, Butterscotch Krimpets and even scrapple, and says he sells prints of them to Philly expats all over the place.

Geno says he's had a lot of requests for a cheesesteak, but has been procrastinating. For one, it "starts off hot, and within probably 20 minutes you're looking at a complete change in temperature, which could change how it looks." Plus, it's tough to find a cheesesteak that fits his requirements of delicious and good-looking.

But Geno keeps coming back to bacon in life (during this interview, he munches on grilled cheese with bacon and tomato between questions) and in art, "even though I'm well aware that the trend is over - or should be," he laughs. Over the last year, he's been incorporating the red-and-white patterns into larger, more abstract drawings that he says some people have mentioned remind them of landscapes. The wavy striations of bacon continue to be enticing subject matter - and to bring home the you-know-what.